Author Richard May and IndiGo Marketing share info about new collection of short stories, Gay All Year from NineStar Press! Read about the 12 story collection and learn more about the author's writing process on penning conflict! Plus, enter in the $10 NineStar Press gift code giveaway!

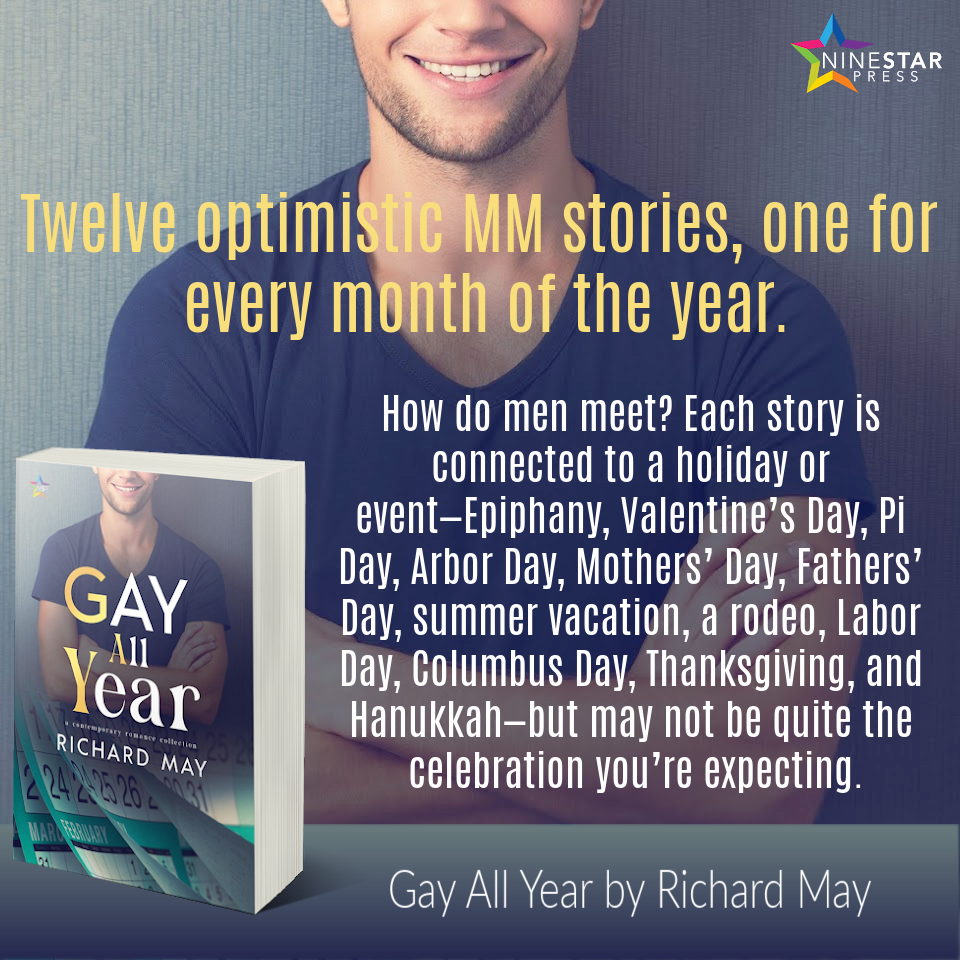

Title: Gay All Year

Author: Richard May

Publisher: NineStar Press

Release Date: August 17, 2020

Heat Level: 3 - Some Sex

Pairing: Male/Male

Length: 78700

Genre: Contemporary, LGBTQIA+, Contemporary, romance, short stories, gay, bisexual, interracial, age-gap, slow burn, friends to lovers, BDSM, Dom/sub, humorous, multiple partners, priest, military, Native American, law enforcement, bereavement, daddy issues, men in uniform, Hanukkah

Synopsis

Twelve optimistic MM stories, one for every month of the year.

How do men meet? Each story is connected to a holiday or event—Epiphany, Valentine’s Day, Pi Day, Arbor Day, Mothers’ Day, Fathers’ Day, summer vacation, a rodeo, Labor Day, Columbus Day, Thanksgiving, and Hanukkah—but may not be quite the celebration you’re expecting.

Neither may the men, and when these men meet, attraction does not always equal love—at least immediately—but chemistry finds a way.

Excerpt

Gay All Year

Richard May © 2020

All Rights Reserved

I never meant to live in San Francisco again, but here I was. At first, it was just a visit but when I saw how advanced the effects of my mother’s lung cancer were, I decided I couldn’t leave her to institutional caregivers and fly back to Boston, so I took a leave of absence, and then I telecommuted, and finally, my company offered me a transfer to the office in Menlo Park.

I also never expected to be inside a Catholic church again, but here I was. I had successfully avoided them in Boston, which is no easy trick when you’re Irish and raised Catholic. But now, I was back inside Saint Paul’s, fulfilling a deathbed promise to my mother. “Don’t blame God,” she had advised between wheezes and made me agree to go to mass. I wanted to scream. Of course, I blamed God and every fucking priest and every fucking Catholic in the world, but I bit my tongue and said I’d go, thinking her funeral mass would fulfill the promise. “And my funeral mass doesn’t count,” she’d said with the remainder of a twinkle in her eye. Trapped—and I didn’t even get to scream.

I had put it off for six months until I’d run into Mrs. Andreozzi on Tuesday past, and she’d mentioned Saint Paul’s had a new priest. “Very handsome,” she informed me as if that were enough of an inducement for a gay twentysomething male. And perhaps it was because the very next Sunday I entered the building, genuflected toward the altar, crossed myself, and took a seat in a pew.

There was an excellent turnout of ladies and gay men. And Mrs. Andreozzi was right: the new priest was very handsome. He was a tall man, with dark wavy hair combed straight back from his forehead, regular features, and noticeably wide shoulders. Nothing at all like Father Michael, with his thinning red hair, sallow complexion, and sagging jowls. I hoped he was different from Father Michael in other ways as well, for the altar boys’ sakes.

After mass, I tried to slip past the line of parishioners telling the new priest how much they liked this or that, but he stepped away from an older woman in midsentence to intercept me.

“Thank you for coming,” he said, barring my way with his conspicuous body and extended right hand. “Father Adrian Doyle.” I shook the hand hesitantly. Touching a priest was, and probably always would be, disgusting to me. Father Adrian’s hand was warm, but then so had been Father Michael’s.

“Stephen Kinney,” I said. The priest’s bright-blue eyes momentarily ceased sparkling. Apparently, he’d heard the name before. I’m sure he has, I thought with satisfaction.

“Good to see you, Stephen. See you next Sunday,” he said, his eyes recovering. He gave my hand a final shake and went back to his line of well-wishers. I walked outside without a commitment, continued down the steps to Church Street and around the second corner to my parents’ house. The park across the street was full of dogs, kids, and adult supervision. I had been one of those kids once upon a time.

I had mostly happy childhood memories and was on quite a nostalgia trip, integrating my things with those of my parents and grandparents. The park was certainly convenient for walking Boris, my mother’s old and needy dog. Why she wanted a Russian wolfhound neither my sister nor I quite understood. It had always been Irish setters while our father was alive. Still, after Mom passed, Anne Marie and I fought over who’d get custody of Boris. Nothing else in the estate mattered as much. I won because I was already walking the dog on a twice-daily basis, feeding him, and acting in loco parentis. My sister lived outside Chicago. If the trip east didn’t kill Boris, the Midwestern winter would.

Monday’s alarm woke me from disturbing dreams vaguely remembered. Men in black, oppressive shadows, Father Adrian naked. The latter image disturbed me most of all. I rushed to be vertical and tried to ignore my erection.

After struggling into jogging clothes, I opened the door for Boris’s stroll to the dog run. Immediately, an unfamiliar tenor yelled “Stephen!” at me. One of a crowd of runners passing by was waving. “Father Adrian!” he shouted in explanation, pointing at his chest, which was already eye-catching enough, even in a baggy sweatshirt. I waved back in a jerky side to side motion and watched the healthy bodies disappear. The priest’s butt was obvious in his skimpy running shorts, shifting left and right, left and right. Lustful thoughts came to mind. “Good God,” I said out loud. Boris whined. “Yes,” I agreed. “Let’s have none of that. Come on, boy.”

The old dog broke into an eager amble across the street. After a few minutes sniffing this fascinating scent, inhaling that arousing aroma, and doing his business, we recrossed the road. I let Boris in the front door and took off at a trot toward Sanchez. Of course, I ran into the Saint Paul’s joggers on their return trip.

“Join us!” the priest yelled, his tousled hair and happy face strong inducements. I heard several other runners second his call, which surprised me, given what I’d cost them. Misery loves company, I suppose, or maybe just following the lead of their priest. Still.

I was about to ignore all of them when someone dropped out of the line and yanked me into it. “Tony!” I yelped. Tony Rodriguez, the boy I’d had a crush on in sixth grade. The man who’d stood by me during the lawsuit. I assumed he’d left town. He hadn’t been at my mother’s funeral, and I hadn’t run into him at Safeway or Royal Cleaners.

“I’ve been in Iraq, and Marylee was at her mother’s,” he exclaimed as if he read minds. Oh, right. He was in the National Guard.

I took up the rhythm of the run, Tony’s admirable thighs racing alongside mine.

“Aren’t you almost done?” I asked, looking for an escape route.

“I wish,” he said, flashing the ten-thousand-dollar smile Dr. Davis of Twenty-fourth Street had given to both of us.

I looked ahead at the priest. “What do you think of the new guy?”

“He’s good,” Tony said, between inhales and exhales. “Up on technology.”

“I thought his Epiphany homily was good,” I said. “Especially the part about everyday epiphanies.”

Tony nearly stopped running. “You went to mass?” he said, looking at me as if I were lying.

“I promised my mother.”

“Uh huh,” Tony grunted. Then he gave me a grin. “And Father Adrian is a good-looking dude,” he said. Just as quickly, his face collapsed in dismay. “I’m sorry, Steve.”

I kept looking ahead, which is what I’d told myself to do after I stopped going to church. The priest’s butt was obscured by those of less worthy men. “No worries,” I told him, but it might not have been loud enough for Tony to hear. In any case, we talked of other things before he peeled off for home a few blocks later.

“Be sure to call me about that beer!” he yelled. I gave him a thumbs-up. If only he were gay, I thought for the thousandth time.

The rest of us finally reached the steps of Saint Paul’s. No one else had spoken to me since Tony had left for home and a shower. At the church, I meant to follow his example, but Father Adrian held me back. “If you ever want to talk,” he said. His fingers gripped my arm with familiar strength and uncomfortable insistence.

“I did my talking to the attorneys,” I replied and pulled out of his grasp. His face was even more handsome when less under control.

“My offer stands,” he said, his lovely mouth now grim. “Don’t let the crimes of a few evil men get in the way of your relationship with God.”

I laughed in his face. “A few? See you later, Father.” I trotted south without looking back.

I had been a cute, blond-haired boy of nine when I came under Father Michael’s auspices. I was twenty-four when I organized other boys who’d become his prey to sue the diocese. There had been a settlement; the church knew it couldn’t win. I bought the condo in Boston with my portion of the proceeds.

However, later that day, Father Adrian’s offer was codified in a text.

Good to see you at church, Stephen. Hope you’ll be with us again next Sunday. And, if you want to talk, my door is always open.

He gave me a phone number. The question was, how did he get mine?

I should have deleted the text but didn’t. I was impressed he spelled my name correctly and by his follow-up. In fact, I kept rereading it until I finally called the number. Mary Flannery answered. She had been the parish secretary for decades. After I said my name, there was a pause before Mary responded.

“Is Father expecting your call?” she asked with an icy edge.

“Yes,” I said.

“Is this still about—” she began but hushed herself. “Just a moment, Stephen.” She put me on hold. I wondered how much it cost her to say my name.

“Stephen!” Father Adrian’s happy voice shouted into the phone. Credit him for enthusiasm.

“I’d like to have that talk,” I said.

“Good,” he answered after taking a quick breath. “Good,” he repeated more optimistically. “After mass? Which one do you—”

“I’ll see you Sunday at noon,” I told him. “On the steps.”

“Better make it twelve thirty in my office.”

“No!” I said, much too loudly. Mary Flannery might have heard me, if she were listening. I had no intention of being alone with a priest ever again.

“Where then?” he asked, sounding irritated.

“In the park. Twelve thirty is fine.”

Purchase

Author Visit

Writing Conflict in Fiction

I don’t set out to write “problem” fiction, stories about the difficulties of life. Conflict isn’t the first tool I pull out of my literary toolbox. My work is about how Gay men meet each other and begin relationships. I try to write about real life, even if it’s science fiction. But there is conflict in my writing because conflict is part of life. It’s part of encountering people. Differences arise or are highlighted when you meet other humans. Bridging divides is essential to developing relationships.

“Garden Party” may be the most difficult story for readers in my new collection Gay All Year from NineStar Press. It began with a visual, as most of my stories do, not a problem. The visual was the photo of a young man of ambiguous racial identity. The story the photo started telling me was about a man of mixed-race background who inherits what had been a Mississippi plantation worked by slaves. His parents are dead. His mother’s line is African-American. His father was a descendent of slave owners. He has brought his maternal grandmother to live with him at the family home, Beaulieu. Over Labor Day his cousins from the paternal side of his family come for the annual picnic. They are blond; he is dark. They are visitors; he owns the place.

The story is told from the point of view of a white lawyer from Memphis, invited along by one of the cousins. I wanted to explore the attraction felt by a white man and a black man in the new South. I also wanted to write about the subtle and not so subtle racism that exists in white people. I didn’t want to hit anyone over the head but, when you read the story, the racism is clear. It is the conflict of the story. The protagonist becomes more aware of the racism of the friend who brought him to the party and in himself. His greater self-awareness begets self-criticism, which is the beginning of growth. This has to happen if the mixed-race character’s attraction to him is to be believable. There’s a conflict for you.

All the other stories in the collection have conflict too, but it’s usually quiet because that’s the way my stories are. There is no flashing sign Conflict Ahead! One story I wrote for another collection was criticized because “nothing happened. 3.5 stars.” I’m not unhappy with 3.5 stars out of 5 but do disagree that nothing happened. What happens is that the two men meet, are attracted, do things together, and become romantically involved. That’s not nothing. No bomb throwing and only angst but who needs either of those? I don’t and neither do my characters.

Most of the stories in Gay All Year have more apparent conflict than that story. A priest who wants to maintain his vows and a man abused by priests as a boy are attracted to each other. Big conflict! Others involve an Indigenous man and a white police officer, men of radically different cultural backgrounds, men who encounter each other in a graveyard while grieving for lost loved ones, the imposition of will by an Alpha male.

Life is real. Part of that realness is that most conflicts between people are not huge. They are smaller, quieter, more subtle. Some are not of course. I’m working on a novel in which the central characters, white and black, have a much more violent conflict to overcome: white racial prejudice and black anger. Those are conflicts real people have to face and resolve in our time. I write romances about real people.

I want to show that anyone can find love anywhere. That is what I believe. That is what has happened to me. It may be unlikely love in unexpected places. The real people will have real differences, but love isn’t an intellectual act. Opposites do attract and opposition is conflict or will inevitably lead to it. The story that results may not be Clash of the Titans but all authors hope you’ll read our work and enjoy it anyway.

Meet the Author

Richard May’s short fiction has been published in his collections Inhuman Beings: Monsters, Myths, and Science Fiction and Ginger Snaps: Photos & Stories (with photographer David Sweet) and numerous anthologies and literary periodicals. Rick also organizes two book readings at San Francisco bookstores, the Word Week annual literary festival, and the online book club Reading Queer Authors Lost to AIDS. He lives in San Francisco.

Tour Schedule

Giveaway

a Rafflecopter giveaway